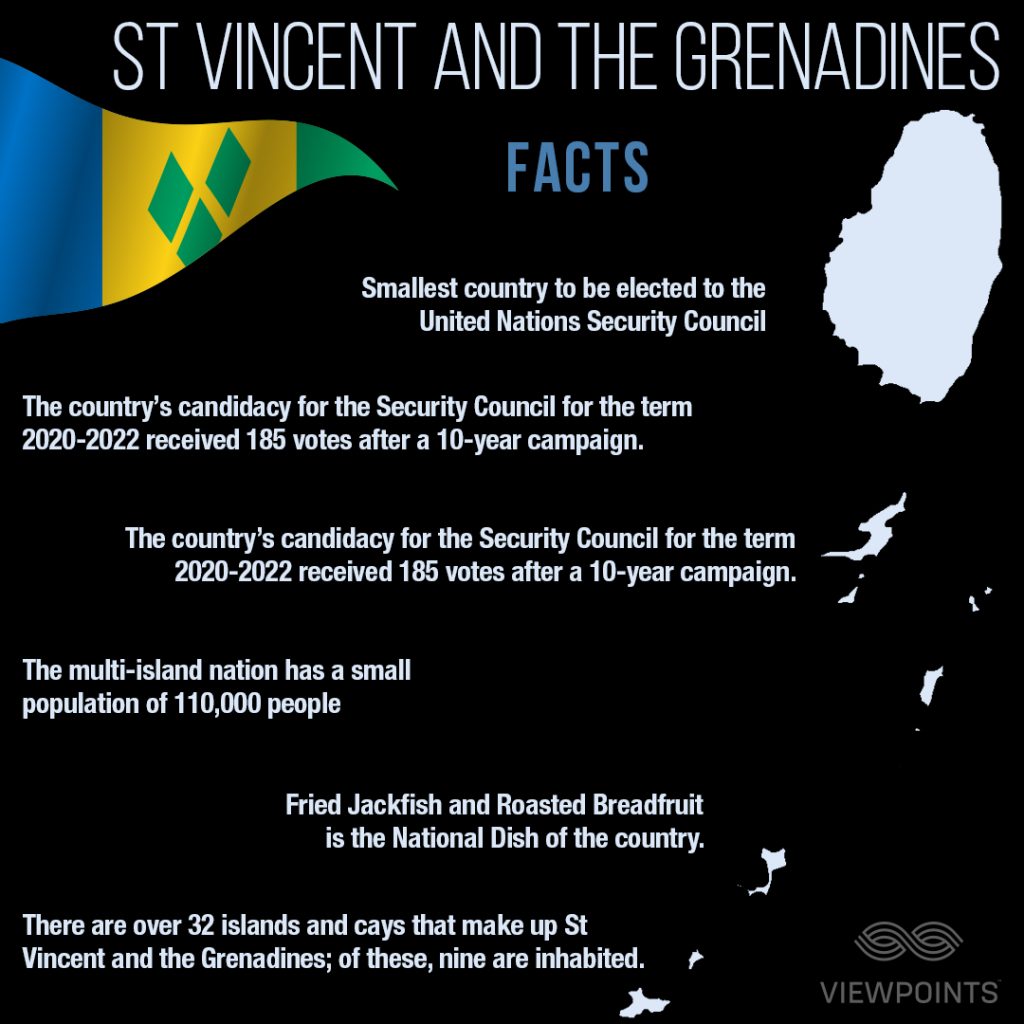

When St Vincent and the Grenadines (SVG) begins its two-year tenure on the UN Security Council on January 1, 2020, the government and people of the country will be assuming a role on the world stage beyond their wildest imagination.

I congratulate the government for its candidature and successful campaign in the UN General Assembly. Serving on the UN Security Council is a daunting undertaking that poses many challenges, especially for a small country with limited human and financial resources. Furthermore, SVG will be one of five new members among the 10 elected, having no prior record or institutional memory of service on the council, unlike the five permanent members with the advantages of being fully resourced, institutional experience, and deep knowledge of the issues on the council’s agenda.

SVG must remain cognisant that membership on the council is not only to serve its own, or CARICOM’s, interests, but, as one of two representatives of GRULAC -the 33 members of the Latin American and Caribbean Group. GRULAC is not homogeneous, and, considering the deep divisions on Venezuela and other emerging issues in the region, SVG will be traversing a minefield.

Also, every member of the council is obliged to engage on all issues on its agenda and uphold the council’s charter responsibilities for the maintenance of international peace and security. No member should sit on the sidelines and be content with a marginal role.

The issues on the council’s agenda are complex and quite challenging for large and small states alike. The stakes are high for the government of SVG, and the challenges will be great.

I recall my marching orders from then Prime Minister P.J. Patterson a few weeks before assuming my duties as ambassador and deputy permanent representative for Security Council affairs at the UN. The prime minister emphasised that Jamaica’s delegation not deviate from our advocacy for security and the protection of human rights around the world; our support for peace and security in Africa and elsewhere; ensuring action on regional issues protected regional interests; and, most important, defending the principles of the UN Charter that safeguarded small countries like Jamaica and the rest of the Caribbean.

Jamaica’s 2000-2001 term on the Security Council was its second. Jamaica’s first was under then Prime Minister Michael Manley (1979-1980). In both cases, Jamaica brought with it an enviable reputation for its effectiveness in dealing with, and leading on, important global issues. Jamaica under Manley and Patterson, two highly respected leaders in the Non-Aligned Movement and the Group of 77 plus China, led these groups in navigating global issues during difficult periods.

Jamaica’s effectiveness in the UN system inspired many governments. The government of Switzerland, during its campaign to win approval in a referendum to determine its membership in the UN, cited Jamaica as an example of a small state’s effectiveness in the UN. Switzerland had, for many years, used its vast financial resources to further the interests of the UN. Yet, the Swiss government looked to Jamaica to inspire its people.

Prior to the referendum, I was asked by the Swiss government to brief a large delegation comprising legislators and other elected officials, civil society, the private sector, and the media brought to UN Headquarters on Jamaica’s role and effectiveness in the UN, as part of the Swiss UN membership campaign. The Swiss expressed admiration for Jamaica’s effectiveness on the UN Security Council and in the entire UN system.

As Prime Minister Patterson wrote in his memoirs, A Political Journey, “In our most recent tenure on the UN Security Council, shrewd commentators marvelled at how a country with such a small delegation could have been so effective in the council’s deliberations during 2000-2001.”

Moreover, as the former prime minister said: “Jamaica’s dominance among non-permanent members on the Security Council on these issues established new precedents and created new dynamics for the council vis-à-vis permanent and non-permanent members.” And, “our principled and steadfast, sometimes uncompromising, defence of justice, gender equity, human rights, the right to self-determination, and the end to impunity for crimes against humanity emboldened other non-permanent members to stand up.”

In recognising our limitations in size and economic resources, former Prime Minister Patterson also noted in his memoirs that “… we sought to maximise the intellectual power with which we were endowed”. I might add that during our tenure on the council, the leadership benefited tremendously from the support it received from a group of young diplomats in Jamaica’s delegation who, most often with very little help from headquarters, shared the burden of preparing our delegation to perform consistently at an extraordinarily effective level.

Given its limited human and financial resources, the government of SVG will need the support of CARICOM and all its members in order to be effective. However, unlike other regional organisations accredited to the UN in New York, CARICOM has consistently failed to have quality or effective representation at the UN. And, with the diminishing influence and marginal respect on the world stage for many of the current Caribbean leaders, the governments of the region have very little to offer.

Traditionally, Caribbean nationals in the UN system have been very supportive of Caribbean delegations. There are also Caribbean individuals in the diaspora who could be supportive. It will be SVG’s challenge to engage with them.