In violence studies, gangs are known to adapt in many ways. They relocate, change shape, go underground, change their members, change their means of income, become more structured or lose structure, rely more heavily on corruption or public servants, kill and bury their victims to make the public think they are inactive, and even contract their killings to independent professionals.

In this way, they revel in the fact that they are smarter than government agencies. The biggest problem to us as Jamaicans is the first of the ones I have outlined: relocation. The most popular action is to move to peri-urban or rural areas. When this is done, government agents have a wider area to cover – and the problem becomes more expensive.

Once you embark on suppression, you must have a predictive map of gang movement. Remember that in small countries, the rural areas are ‘gang covers’. Gang members have relatives and friends in these rural communities. We call these ‘Importees’. Each time military and paramilitary operations attack gangs in urban spaces, the connected peri-urban and rural areas suffer immensely from the importees that rush in.

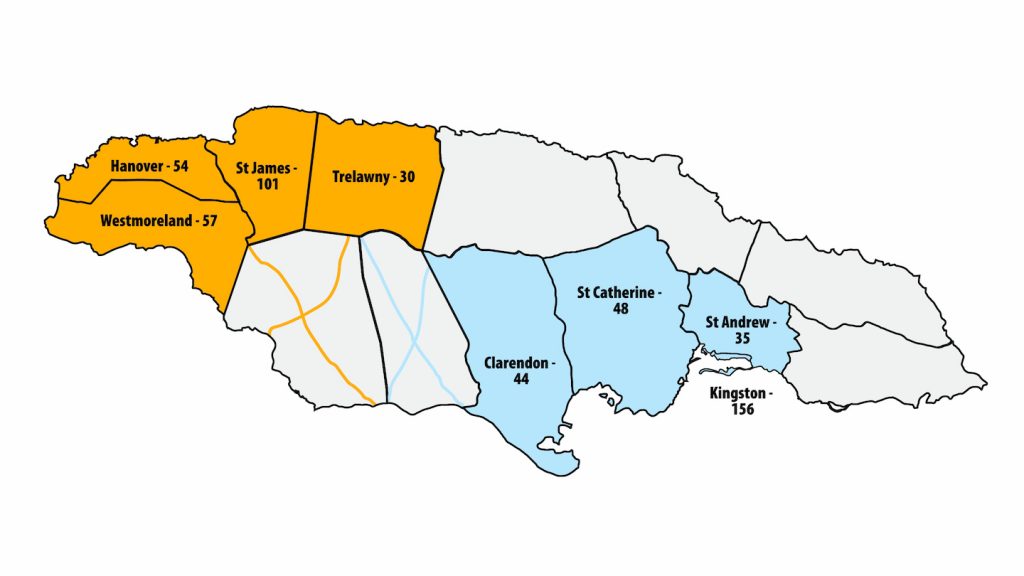

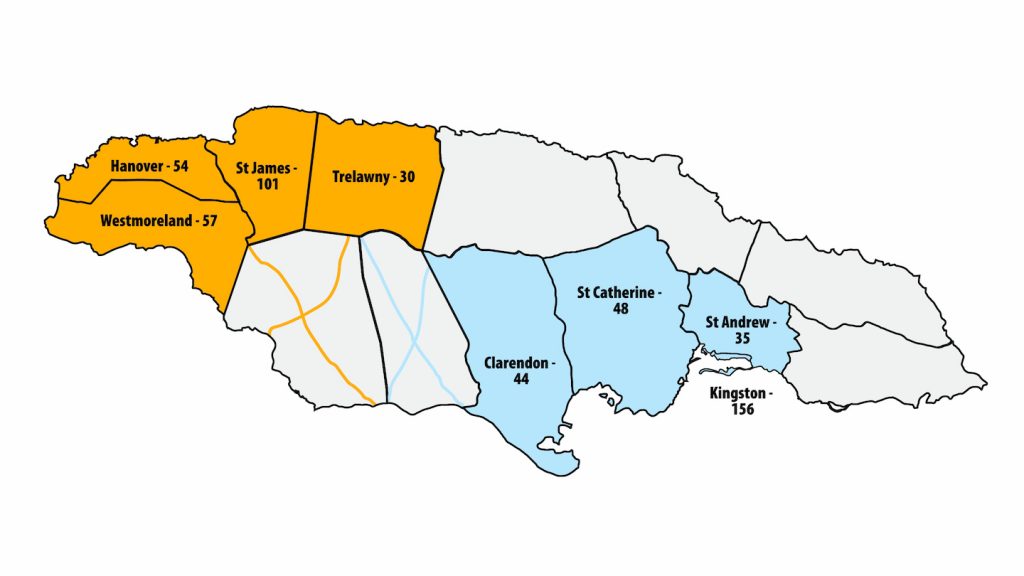

Jamaica has two gang hubs, as shown below. The spread of gangs is directly related to government strategies in the past decades. Very soon, there will be no area left free of gang activity, open or covert. The blue hub started in Kingston and has spread as far as Manchester. The yellow hub started in Montego Bay and has gradually started to engulf St Elizabeth, the breadbasket of the country. The northern and eastern aspects are not free of gangs, but those are adolescent. The figures in each parish in the map represent the average homicide rate for 2010-2016.

Violence models are complicated and require equally sophisticated plans to address the problem. They rest on the core assumption that violence is a by-product of social ills. Hence, there must be changes in social structures in order to solve the problem. The model below represents the problem in Jamaica, Belize and Trinidad. In the simplest terms: Jamaica, Belize and Trinidad have violent histories. These colonised states have segmentary factional politics. This means that citizens are Labourites (JLP) and Comrades (PNP) before being Jamaicans.

Such factions provide a wide space for corruption, and encourage a lack of development focus on the part of the government. This is because the factional frame allows people to suffer from what is called victory addiction. In a system of victory addiction, the winner has the power to do as he or she pleases. The loser will wait to get the chance to win, and, if he or she does, will proceed to do as he or she pleases.

This means that the party in power is allowed to do various corrupt acts, and, when confronted by a few, can point out that the previous government did the same. In short, the country lacks a pressure group as each set of supporters is not backing strategies that will help the country, but those that will help their party win, which will continue their victory addiction. This cultural behaviour leads to successive weak and corrupt governments. The bad news is that gangs thrive in such settings. This is why violence experts declare that we cannot have a gang problem without corruption.

On the right side of the model, we can see absent fathers and unsupported mothers. These are direct results of slavery. Absent fathers imply that more boys will have to hustle to support their families and themselves. Many will not get the chance to complete secondary school, and the majority will not even consider going to college, as their gender roles must be met, which is to support their mothers.

However, without support, mothers do various ‘slavery-creative’ acts to keep their families alive, including torturing boys to stay away from gangs. However, this pushes them into gangs instead. The gangs, therefore, serve as the replacement family frame for that which was destroyed by centuries of torture. The result is that scared security officers attack organised youth, who, in turn, justify attacking the State’s agents. The sad reality is that in Jamaica, Belize and Trinidad, both the police and the youth come from underserved and neglected communities. What is needed is appropriate funding to these communities that suffer continuous attacks.

Most repeat killers were tortured by their caregivers. The term ‘torture’, in this context, means prolonged severe physical and/or psychological harm. Between 2004 and 2014, I managed to convince 17 dons with power over 28 inner-city communities in Jamaica to allow me to profile the young men under their influence. These were combatants between aged 15-34. Over the period, we covered 2,316 young men. Then we did Trinidad (795) and Belize (509).

In the Jamaican data, 6% of the young men studied had killed one or more persons, compared to 5.5% for Belize City, and 5% per cent for Port-of-Spain. In Port-of-Spain, 31% of all inner-city males reported being tortured growing up as boys; Belize City (35%) and Jamaica (46%). The more violent the ecology, the more boys were tortured as caregivers struggle to keep them away from gangs. Of critical importance is the fact that 67-69 per cent of those who had killed someone reported being tortured, and all who had killed more than three persons (including women) were tortured by their desperate mothers. All violence-reduction strategies in our region must, therefore, have major investments in parenting, with a focus on at-risk mothers who certainly will create at-risk boys – who are favourites to join gangs.

Finally, all violence-reduction plans must address violence at its three levels. These are broken down in the table below. Again, social violence is caused by social ills. These ills begin at the foundation: family, education, community fractures, identity crises, and political dependence. Fractures at the primary level impact the secondary level – economics – and lead to tertiary fractures or conflict.

In order to reduce violence, we reverse the process. We begin with ceasefire. This means that suppression can have a place. However, once the ceasefire is achieved, the economic and social restoration must begin with focus on redeployment, jobs, and restructuring of communities. This allows us to focus on long-term goals such as reducing the recruitment pool. This implies getting boys back in school.

Currently, this is a crisis, and the core ganglands in Jamaica, Belize and Trinidad have large proportions of males out of school between the ages of six and 18. It also means that we begin the long march to the empowerment of our women and men – and this means the reconstruction of communities. Ministries such as those relating to education, youth, and social development would drive the economy. These changes would lead to a gradual reduction in expenditure on weapons and other material used by the state to suppress the actions of its populace.

| Type of Impact | Characteristics | Contributing Interventions |

| Primary (Foundation) | Preventative: structural and long-lasting | Individual-level: – Education or training\ – Parenting skills – Preventative alternative justice interventions – Mentorship Community-level: – Economic opportunities that affords ontological security to all – Changing violence norms – Interventions in community institutions |

| Secondary (Visible/Redeployment of combatants) | Curative reduction: visible and immediate | – Conflict resolution – Counselling – Social welfare – Jobs/project |

| Tertiary (Relief/adaptive) | Temporary relief/crisis adaption | – Peace treaties/ceasefires States of emergency and other forms of violence suppression – Relocation of problems – Group praying and peace marches – Gun amnesty |

Table: Primary, secondary and tertiary violence-reduction plans.

Herbert Gayle, PhD, is an anthropologist of social violence.