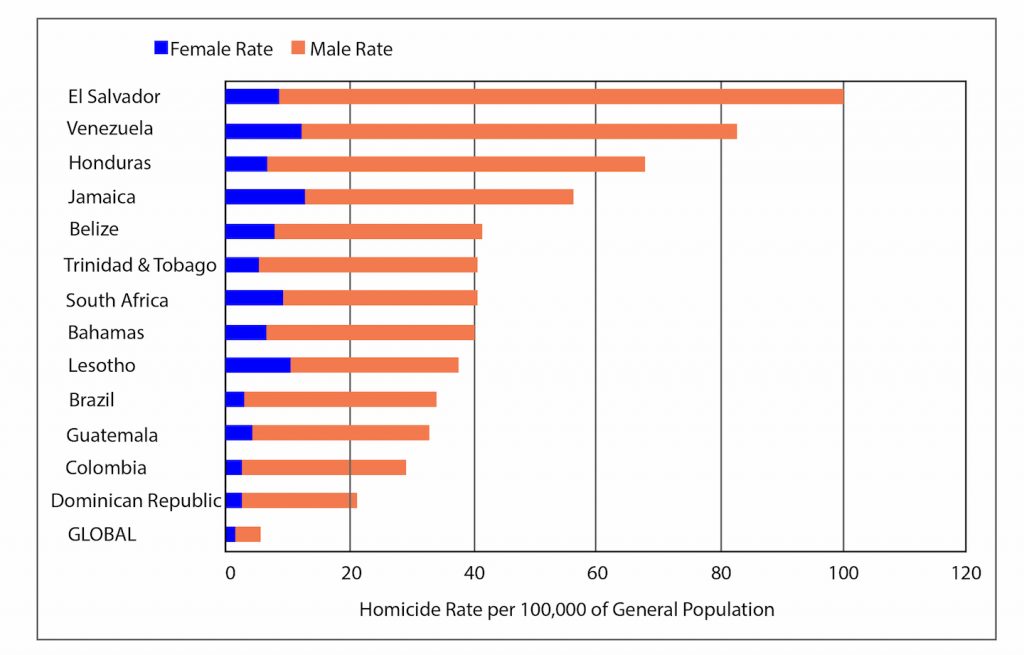

The book’s second chapter, entitled, ‘Why is Democratic Jamaica so Violent?’ has the same two-fold purpose. It addresses one of the island’s greatest problems: its abysmal level of violence, the fact that it is among the world’s 10 most homicidal countries.

However, tackling this problem allows us to probe an equally troubling, broader issue: the question of whether democracy is itself inherently violent. Thus, the sub-title of the chapter: “Whatever happened to the ‘democratic peace’ thesis?” This is a vexed issue in political science and political sociology. It is assumed, by many that democracy is inherently peace-promoting, that indeed, it is premised on the very idea that conflicts can, and should, be resolved amicably through negotiation and peaceful, participatory give and take.

‘Jamaican democracy is alive and well; people are thoroughly committed to it, and play by the rules of the democratic game in all fundamental respects.’

The dilemma Jamaica immediately poses is that it has a vibrant, working democracy. This is no illiberal ‘phoney democracy’ as the economist once called them. Jamaican democracy is alive and well; people are thoroughly committed to it, and play by the rules of the democratic game in all fundamental respects. Jamaica’s turn-out rate at elections, until recently, put America and many of the advanced democracies to shame. Furthermore, Jamaican democracy has repeatedly passed the ultimate test of genuine democracies: it has had numerous changes of government resulting from the people’s vote.

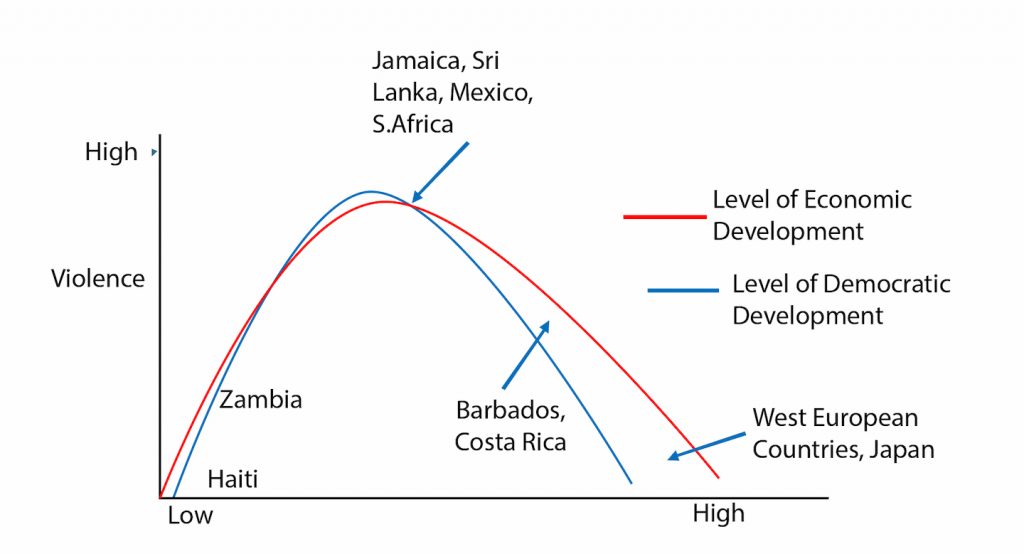

So, the question Jamaica poses is quite simply this: could it be that democracy, far from being inherently peaceful, is in fact, inherently violent? Is Jamaica violent, not in spite of, but in good part, because of its deeply rooted democracy? Chapter 2 attempts to answer these questions by probing deeply into the theory of what has been called ‘the democratic peace’, and the answer we arrive at is somewhat disturbing, if not for democracy in the advanced world, most certainly for democracies in post-colonial societies.

My argument, in a nutshell, is that the intersection of the transition to a fully mature democracy and a transitional, and stalled, economy, is a volatile one that is associated with violence all over the world. However, in addition to this violence-inducing intersection, Jamaica also has independent courses of violence coming from its violent past, its drug culture, and from the socialisation, and miseducation, of its children.

In Chapter 3, I examined yet another claim about Jamaica’s unusual pattern of development. In an early work, the eminent labour economist, Guy Standing, had argued that Jamaica was unusual, not only among post-colonial societies, but in the development of capitalism, in the fact that its male labour force was chronically un-proletarianised and, further, that women had been brought into the labour force and proletarianised to a far greater degree than men.

If this were indeed the case, Jamaica would have gone against a pattern of development in the sexual division of labour during the rise of capitalism that is regarded as something near to an economic law by labour economists. This is the finding that it is men who first experienced the disciplining of the capitalist labour force during which women were economically marginalised as their traditional patterns of employment were disrupted, only much later re-entering the labour force as the economy entered a more mature phase of development.

As it happened, I had collected a large body of data on the Jamaican post-colonial labour force during the same period that Standing had studied, which I had used mainly for my policy work as an advisor to the then prime minister and government of Jamaica. This chapter replicates Standing’s study and largely unchallenged findings. What I found partly supports Standing’s argument regarding the rapid incorporation of women in the labour force, but undermines the finding that men were under-proletarianised.

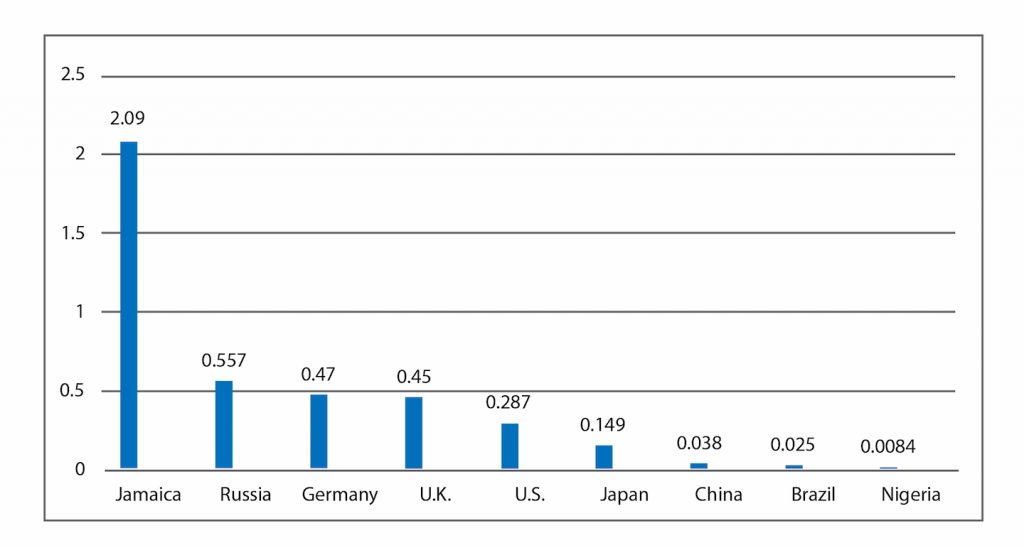

More importantly, I found a far more complex post-colonial system of labour exploitation that had its roots deep in the colonial and slave past of the island. Jamaican working-class women have always faced a triple burden of hard labour in the workforce, at wages much lower than men for the same work, even though they are usually more literate than men, combined with sole responsibility for child-rearing and very fraught gender relations that too often end in violence and death. Indeed, one of the most horrendous aspects of Jamaican violence is that the island currently has the highest rate of female homicide in the world. Jamaica is the most dangerous place for women in the whole world.

Source: Orlando Patterson (2019), The Confounding Island: Jamaica and the Postcolonial Predicament

The second part of the work shifts to an emphasis on more cultural processes during the post-colonial period. Chapter 4, ‘Why do Jamaicans Run so Fast?’ examines what is likely the most confounding puzzle about Jamaica to non-Jamaicans all over the world. How can a little nation of fewer than three million people, out-perform the rest of the world in sprinting? How and why, in terms of Olympic medals won, can Jamaica out-perform countries hundreds of times its population, size and wealth? The tempting answer, that Jamaicans are endowed with some speed-gene, has been shown by the most rigorous scientific studies to be without foundation. Nor, is the answer in the yams we eat. I grew up in Clarendon, having all the yellow yam I could eat, yet I couldn’t run to save my life. If it’s not in the yams or their genes, then the answer must be social and cultural, and I argue for just such a conjunction. My explanation, in a nutshell, is that Jamaica’s athletic supremacy is a remarkable case of successful institution-building on a grand scale.

Source: Orlando Patterson (2019), The Confounding Island: Jamaica and the Postcolonial Predicament

At the start of the 20th century, a series of quite adventitious factors set in motion a path-dependent process that culminated in the globally unprecedented institution of Champs. Actually, several institutional paths converged and complemented each other in a cascading process, leading to national athletic excellence. Among these was the public health revolution, mentioned earlier, that produced an unusual number of healthy young bodies, rarely found in a poor country. Taking advantage of this was the extraordinary social welfare and community development programme, developed by Norman Manley and a talented number of community leaders such as Thom Girvan.

Norman Manley’s role in this inter-institutional development cannot be over-emphasised. Believing strongly that healthy bodies and sports, bred both healthy minds and a healthy, emerging nation, he embodied in his own person the values and educational goals he so vigorously pursued. Jamaica is the only modern nation whose founding father was also a track star. He was the fulcrum of a remarkable number of athletes-turned-coaches who were role models for later generations of younger athletes.

By the late ’30s and early ’40s, the institutional path to greatness was locked-in, both educationally and culturally. Reinforcing these developments was an important cultural factor, what I have called the combative individualism of Jamaicans, a predisposition rooted in centuries of resistance to unrelenting corporate and state-sponsored violence (Jamaican prisoners were sentenced to, and lashed with the cat-o-nine as late as 1990!). It is not accidental that Jamaicans excel in running rather than other more group-oriented sports. A fair number of studies have shown that sprinting tends to attract more individualistic personalities. It should also be noted that this same combative individualism is implicated in our propensity to violence.

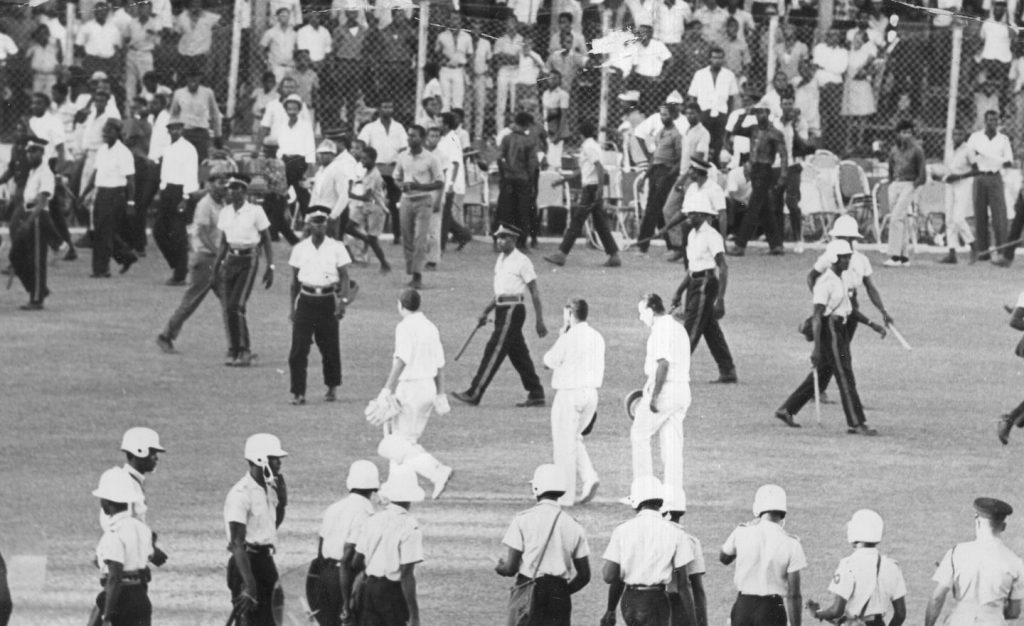

Chapter 5 is entitled, ‘Why did Jamaicans Riot at a Cricket Match against England’. The puzzle here is why did Jamaicans (and West Indians more broadly) engage in a series of riots during international test matches with England. More particularly, why did these riots take place only during the late colonial and early post-colonial period? And why only against England, especially after the British had eagerly left or expressed their intention of closing up the colonial shop as expeditiously as they could?

Sabina Park in 1968.

I show that these riots had less to do with the British visiting teams, and more to do with the nature of Jamaican (and other West Indian) societies, especially the gross inequalities in the island, and the ways in which these inequalities were expressed in terms of the racial and colour values, as well as the different class cultures of what is essentially a tri-cultural society, one of which (bourgeois Anglo-Jamaican culture), was esteemed, the others (the creole Afro-Jamaican cultures of the rural and urban masses) denigrated. In the course of this analysis, I introduce a concept of broader significance for cultural analysis, what I called a transubstantive symbol, one that stands for and actualises itself. The test-cricket match, I argue, was symbolically constitutive of every tension in Jamaican society which normally remained dormant and could even symbolically canalise and control inter-group violence. All this changed when the home team was being whipped by the visitors, their heroes devastated. At such times, the symbolic structure of the game was totally transformed and became explosive, the details of which I do not have the time to get into here.

Besides outrunning the rest of the world, the other great puzzle that Jamaicans present to the world is the astonishing success of their popular music, especially reggae. When, near the end of the last century Time Magazine named the album, Exodus, by Bob Marley and the Wailers, the greatest album of the century, few aficionados of popular music were surprised. Thirty-one years after his death, Marley, along with a large number of the island’s other performers, are global household names. What is less known is that, even before reggae and dancehall, Jamaican music had had an outsized influence on global popular music. Thus, the first album in the history of music to sell over a million copies is a collection of folk-songs and folk-inspired compositions, not from Europe or America or Asia, but from the mento-peasant music of Jamaica, Day Oh!, sung by the Jamaican-raised, Harry Belafonte.

Jamaica’s global musical successes are also not to be belittled as simply a case of individual talent. As with our supremacy in running, it is the result of hard work and creative institution building. Jamaica’s musical success was initiated by, and largely the product of a bottom-up movement. It is significant that this is also true of the more technical, production end of the island’s music industry. The creation of an internationally competitive music industry in Jamaica, with its own distinctive, globally influential ‘recording model’, was a complex mix of technical, creative, economic and cultural processes, and, as Ray Hitchins (2014) has definitively shown, entailed bottom-up and some top-down interactions between individuals of different classes, colours and ethnicities, commanding different musical, audio engineering, and management skills and access to funds. It is an outstanding instance of learning by doing and of adoption, adaptation and evolutionary change, culminating in the dominant music studios of reggae greats such as Clement ‘Sir Coxsone’ Dodd, Duke Reid, Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, King Edwards, and others.

In explaining the enormous reach of reggae, I was led, once again, to a broader problem of global cultural significance. This is the question of whether globalisation is leading to a homogenisation, or more specifically, westernisation and Americanisation, of the world’s cultures. Many have expressed such fears, not least of all the celebrated German scholar, Adorno, as well as the eminent folklorist, Alan Lomax. I argue strongly against the view, in line with a group of scholars, including the distinguished student of Jamaican music and popular culture, professor Carolyn Cooper, who has emphasised the principle of ‘glocalisation’ in the interactions of western and other musical traditions around the world. Far from homogenising the local music of the world, the diffusion of musical traditions from one part of the world to the other has generated a vast amount of musical creations in which indigenous traditions are hybridised with foreign elements to produce wholly new and exciting creations.

Jamaican reggae music is the near-perfect illustration of this process of ‘glocalisation’. Under the impact of black American music, its musicians created vibrant new music, ska, which soon mutated into what has become known as reggae. But reggae, in turn, was to spread abroad, especially back to America where it was instrumental in generating the secondary ‘glocalisation’ process that culminated in Hip Hop, the great DJ Kool Herc, a Jamaican immigrant (born Clive Campbell), being one of its acknowledged founders. Hip Hop and reggae have later continued to mutually influence each other and, in turn, influence the other popular music of the world in a global wave of tertiary ‘glocalisation’. The same cannot be said of what happens at the bourgeoisie and macro-economic levels of global contact. Here globalisation often does lead to westernisation and especially Americanisation, and such premature modernisations have often proven fatal for the sustainable economic development of post-colonial societies.

The above is Part Two of a presentation by Orlando Patterson delivered at a public lecture on the topic ‘Jamaica and its Post-Colonial Predicament’ on November 29 at the Regional Headquarters of The University of the West Indies. Patterson, a historical and cultural sociologist, is John Cowles Professor of Sociology at Harvard University.

Viewpoints is committed to expanding its range of opinions and commentary. Share your views about this or any of our articles. Email feedback to viewpoints@gleanerjm.com.