There are few places on earth more confounding than Jamaica. A little island barely the size of Connecticut, it has a larger global profile than countries hundreds of times its size. At times celebrated for the spectacular performances of its stars and the worldwide impact of its cultural creations, it is often condemned for the depravity of its gangsters and racketeers, and the failures of its economy. All too aware, Jamaicans, selectively proud of this record, are prone to say “Wi lickle but wi tallawah”.

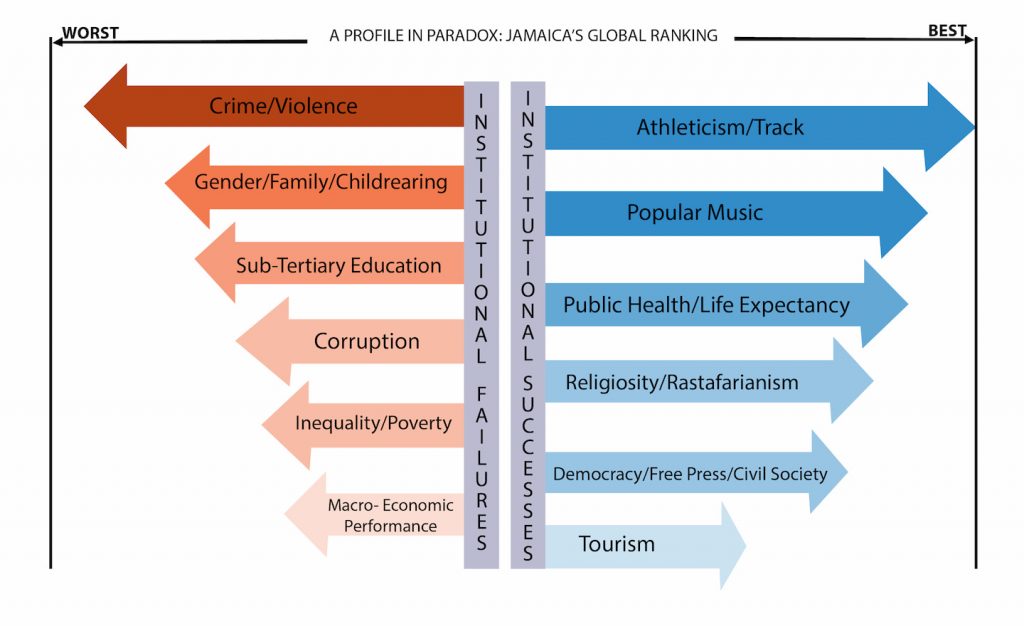

In global comparisons, it has a disturbing way of coming out among the best or worst group of countries. The graph below summarises what I mean. While the oft-quoted claim that Jamaica has more places of worship per capita than any other nation may not be quite accurate (Bermuda and Malta have twice as many), there can be no doubt that Jamaicans are in serious fear of God and, of course, Satan, judging by the numbers in attendance at churches on Sundays and Saturdays, and the wrath and brimstone sermons of its fundamentalist preachers. It has also produced what has become a global religion, Rastafarianism, with followers all over Europe, America and Asia, whose motto is “peace and love”. Nonetheless, it is one of the most violent, reckless and downright sinful of nations; it once had the highest homicide rate in the word, and for most of this century, has remained in the top 10 most murderous places, its “yardies” and posse gangsters even at one time spreading a reign of terror among the drug dealers of America.

A Profile in Paradox: Jamaica’s Global Ranking

Its national music, reggae, is globally influential with its national hero, Bob Marley, arguably one of the world’s most recognisable voices, his message of love, hope and resistance, an inspiration to people of every faith and culture. Nonetheless, the latest version of reggae, dancehall, celebrates violence, Afro-Jamaican ragamuffins, thuggery, homophobia and sexism to such a degree that several of its best singers have been banned from performance in Europe and America.

A little island barely the size of Connecticut, [Jamaica] has a larger global profile than countries hundreds of times its size.

Its track athletes dominate the world, and have run the fastest times on record. Even where it has no chance of winning, it turns up and steals the show, as its bobsleigh team did in the Canada Winter Olympics, and the opening ceremony at the 2018 winter Olympics in Pyeongchang. Though the fastest runners in the world, off the tracks Jamaicans are notorious for being among the slowest people to show up for appointments. Indeed, they take pride in their tardiness, one of the most frequently used phrases in the island’s creole being “soon come”, a disheartening term which can mean anything from an hour to a week, before turning up or completing assignments.

For all its global excellence in athletics and music, the island’s economic performance has been, until recently, very disappointing. To the World Bank, which has expended enormous effort, unsuccessfully, trying to turn its economy around, the island presents an inexplicable economic conundrum which it described, in one of its country studies, as the “paradox of the 1990s”. This is the fact that throughout the decade, (and continuing in the 21st century), although its growth rate stalled or went negative, its poverty rate kept going down, falling by nearly 50 per cent at the same time. This defies all economic logic, and the World Bank cannot explain it. In one report the Bank noted that, “Jamaica’s economic history is a story of paradoxes and potential”. Equally perplexing, is the fact that after several decades of economic stagnation, the island’s economy has suddenly come to life under a new generation of young leaders.

While the oft-quoted claim that Jamaica has more places of worship per capita than any other nation may not be quite accurate (Bermuda and Malta have twice as many).

But defying logic seems to be a perverse propensity of the island, and it is no accident that the term ”paradox” appears so often in experts’ and laymen’s attempts to understand it. Take, as another example, its demographic history. During the first half of the 20th century, Jamaica was an impoverished colony in a neglected part of the British empire, whose governors were prone to dismiss its population as an ‘unruly’, willful and rebellious lot. Nonetheless, an astonishing demographic transition took place during the 40 years between the 1930s and 1970s: the island shifted from having a medieval-level life-expectancy of 36 years at birth to one over 70, on a par with the advanced countries, while remaining poor, a rate of transition greater than that of all but two of the advanced countries of the world. This led the historical demographer, James Riley, to entitle his work – what else – Poverty and Life Expectancy: The Jamaican Paradox.

One would have thought that with so much violence, such poor economic performance, so many head-scratching paradoxes, Jamaicans would be an unhappy bunch of people. Not a chance. The 2016 British Happy Planet Index, rates Jamaicans among the world’s happiest, ranking it 11th of 140 countries surveyed. A columnist in one of the country’s newspapers, Mark Wignall, was understandably led to ask if Jamaicans are happy for the wrong reasons and “could a mentally disturbed man (read nation) be happier than a normally adjusted person”. What is clear is that Jamaicans imagine themselves to be laid-back people. The expression, “Jamaica, No Problem,” rivals the utterances of Donald Trump for sheer self-deluding falsehood, but has nonetheless been embraced with gusto as a national motto. The fact that Jamaica is among the top 10 marijuana-consuming countries in the world (UNDC 2014) may have something to do with this self-perception. Whatever the explanation, a positive attitude may well be best for a country with as many problems and perplexing contradictions as Jamaica’s.

The 2016 British Happy Planet Index, rates Jamaicans among the world’s happiest, ranking it 11th of 140 countries surveyed.

As a Jamaican and a historical sociologist, I have pondered Jamaica’s problems for most of my adult life. My first academic work (Patterson 1967), explored one major source of its problems: that for nearly two-thirds of the 473 years since its European discovery by Columbus in 1494, Jamaica was a slave society – all the more compelling a factor given that the 183 years of British plantation slavery (1655–1838) may possibly have been the most brutal in the dreadful annals of slavery. The British spared no quarter in their extreme exploitation of the island, and their willingness to import Africans as slaves to work the sugar plantations, coffee farms, and cattle pens. For over a century, Jamaica was the most lucrative colony in the British Empire, “a constant mine, whence Britain draws prodigious riches”, according to a contemporary, its trade with Britain outstripping that of the American colonies. It was also “the most unequal place on the planet”, far more so than the US slave South (Burnard, Panza, Williamson, 2017). The economic and physical savagery of the British that made this vast production of wealth possible, took an unspeakable toll on the slave population, which, unlike that of America, never reproduced itself. But the Jamaican slave population did not take it passively.

Indeed, the level of resistance, which took many forms, was perhaps unparalleled in the history of slavery, with the mighty British colonial army at one time forced to sue for peace before agreeing in a treaty to allow the rebels to form their own state within a state on the island, with their own laws and rulers. There is no similar treaty by slave-holding class in the history of slavery — or for that matter, of empire. My first major academic paper was a study of this 90-year rebellion (Patterson 1970).

Ours is a past drenched in blood, like no other place on earth – the swift genocide of the Arawaks, the slow-motion genocide of the Africans. What happened during the colonial period, before and after slavery, is critical for any understanding of the island’s post-colonial history, and the long first chapter of this work explains why by means of an extended comparison with the parallel colonial and post-colonial history of Barbados. However, this first chapter, like most of the others, attempts more. The fascinating thing about Jamaica, and its puzzles, is that they are not only interesting in themselves, but pose problems that are of broader and deeper significance for the entire post-colonial and developing world. Thus, the comparison with Barbados also allows us to address one of the most vexing issues in the study of social and economic development: that of the relative significance of institutions and good policies in explaining successful change. In recent years, the institutionalist approach has gained ascendancy among social scientists. However, the Jamaican economist, Peter Henry, used a comparison of the two islands to argue forcefully that good policies trump institutions. In this chapter, I push back against Henry in favour of the institutionalist position, especially that of Daron Acemoglu and his collaborators, but with several important qualifications that, I hope, improves it. Like all the other chapters in the book, then, this chapter, in untangling the confounding puzzle of Jamaica, contributes to a resolution of broader problems in the development of post-colonial societies.

I have argued that while the British institutional structures brought to the island were superficially similar to those of Barbados and other islands, all but a small elite were largely excluded from meaningful participation in them. Quite apart from the lack of experience in governance among the decolonising elite, the model of political rule presented by the colonial regime augured poorly for independence. There were, to be sure, several persons of great integrity among those leading the country to independence, such as the revered founding father, Norman Washington Manley, but for too many, the path towards tribal politics and self-interested disregard for the common good, was already rooted in the bourgeois-led decolonising movement that coopted the last great revolt for social justice on the part of the Jamaican masses during the 1930s.

The same problem of exclusion from meaningful management roles holds for most of the other important institutions from the colonial era: the civil service, the police force and what there was of an educational system. The conclusions of an important evaluation of the Jamaican civil service by Professor Mills soon after Independence hold true for all the other inherited institutions: “Jamaican civil servants continue to accept the British colonial model. The significance of this fact can only be understood when it is appreciated that the British did not allow local colonial civil servants to take real decisions. Real decision-making was conducted outside the system”. Much the same holds for the police force where British colonial officers as far down the ranks as inspectors, and even sergeants ruled. The experience of my own father, who joined the force in the 1920s, was typical. An intelligent, hard-working man, proud of the fact that he was among the first of the ‘natives’ to make the ranks of detective, he was never promoted beyond the rank of lance-corporal. When, in frustration, he helped lead the movement to unionise the force, he was summarily fired.

Years of protracted legal struggle to win a meagre pension left him disillusioned and alcoholic, resulting in a long separation from my mother. The problems of the island’s present police force can be traced straight back to the leadership vacuum inherited from the colonial past with the withdrawal of the British officers. This is in stark contrast to Barbados where, from early, in the post-emancipation era, blacks replaced working-class whites in the force, their descendants gradually moving up the ranks, resulting in the inheritance of a well-functioning police institution upon independence which, today, solves the great majority of homicides in the island, compared with the Jamaican force’s dismal record of solving crimes.

My conclusion then, is that while institutions are indeed critical, and precede policies in importance, just as important is the acquisition of competence that determines how the institutional game is played. Jamaica’s challenge is not that it does not have the right institutions, but that in many areas, though not all, it has, what has been called an implementation deficit, a lack of the core competencies essential for the efficient management of a successful modern economy. Furthermore, an understanding of this lack of institutional competence has to take account of the island’s past and culture because all institutions are culturally and historically embedded.

The above is Part One of a presentation by Orlando Patterson, delivered at a public lecture on the topic ‘Jamaica and its Post-Colonial Predicament’ on November 29 at the Regional Headquarters of The University of the West Indies. Patterson, a historical and cultural sociologist, is the John Cowles Professor of Sociology at Harvard University.

Viewpoints is committed to expanding its range of opinions and commentary. Share your views about this or any of our articles. Email feedback to viewpoints@gleanerjm.com.