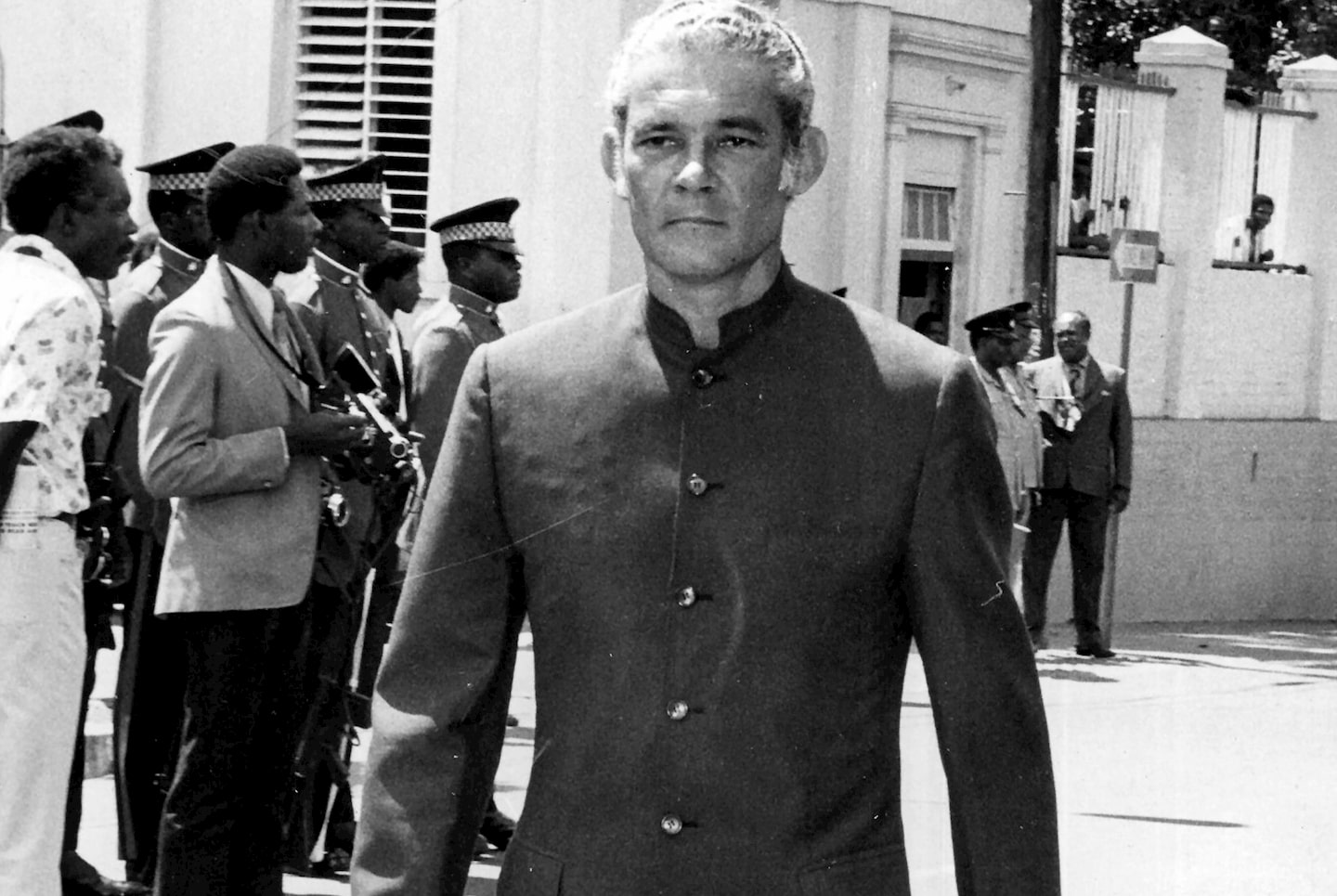

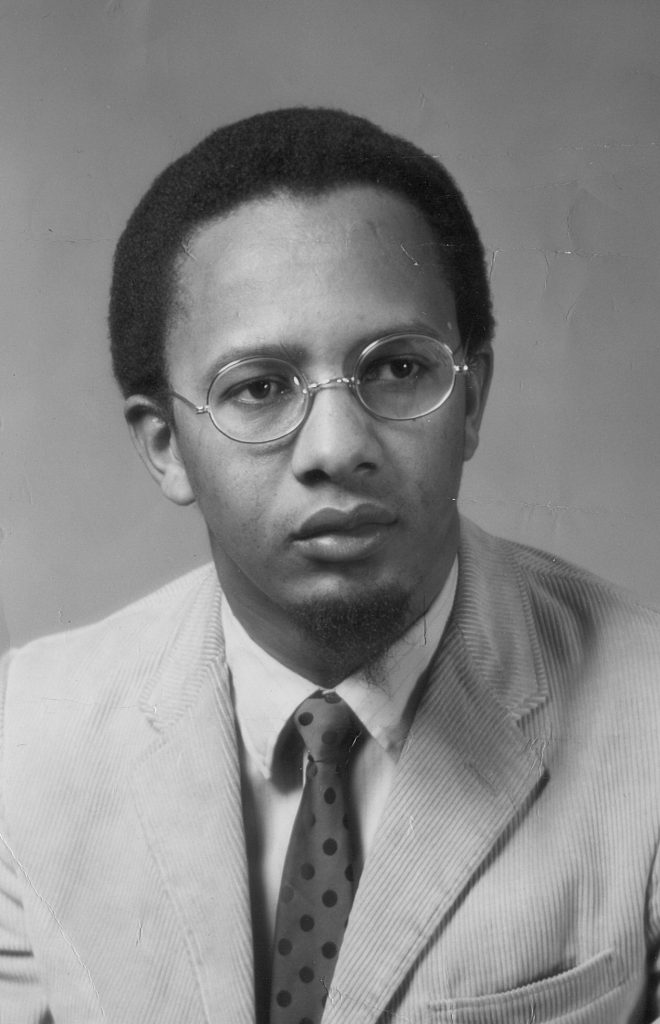

The two chapters of the third part of the work focuses on policy and politics or, more properly, the dominant politician of the post-colonial era, Michael Manley. For eight years, between 1972 and 1980, I was special advisor for social policy and development to Prime Minister Michael Manley, and served on the nation’s Technical Advisory Council. Those were heady days. Although I was involved with a range of policy programmes, my work was focused on the alleviation of the problems of the urban poor.

I had been engaged with the urban poor from my high school days when I lived for over two years in the Jones Town (then known as Jones Pen) neighbourhood, which bordered on the notorious Denham and Trench towns, the latter made famous in the lyrics of Bob Marley. Later, as an undergraduate, I did research on the unemployed youth, and on the newly- emerging Ras Tafarian religious group, being present at the moment of their millenarian crisis when the ship of their God, Haile Sellasie, failed to turn up to take them back to their paradise of Ethiopia, as they had fervently been led to believe. These experiences provided the materials for my first novel, The Children of Sisyphus, written largely when I was an undergraduate at the University College of the West Indies, now The University of the West Indies.

The period that I worked among the urban poor of Kingston coincided with a marked shift among economists and members of the international policy community toward an emphasis on the basic needs of the poor. This came from a realisation that the policies of the post-war era had had little positive impact on the poor and instead, had worsened their condition. Interestingly, a similar renewed emphasis currently animates economists of the developing world, best expressed in Poor Economics by Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee, both of whom recently won the Nobel prize in economics.

The ‘basic needs’ approach of the seventies dovetailed perfectly with the egalitarian emphasis of Manley’s ‘Democratic Socialist programme’. When I explained it in detail to Manley, he became so enthusiastic about it that he instructed me to develop an urban upgrading program in his own constituency, located in the low-income area of south-central Kingston. The centrepiece of that programme was an abandonment of the previous emphasis on the building of housing estates as the way to help the urban poor, a hopeless, wasteful and thoroughly iniquitous approach which resulted in the displacement of hundreds, sometimes thousands, of persons from the neighbourhoods on which they depended for mutual support, in favour of a chosen few who were politically connected to the ruling party. Instead, I set about implementing an upgrading programme that focused on the improvement in sanitation, sewage clearance, water supply, infant daycare, public health, home repairs and aid for the destitute, especially the elderly. The result, it was made clear from the beginning, would be a neighbourhood that still looked like a slum, but one that was far more livable, providing the basics of human habitation and a community organisation directed by local leaders.

My programme failed, even with the initial support of the prime minister who, under pressure from local leaders gave in to the demand for a housing scheme. What was most surprising were the reasons for my failure and the persons who quietly worked behind my back to undercut the programme, many of them loud-mouthed, so-called ‘socialist’ advocates of the urban poor.

The failure of the urban upgrading project is a good example, at ground level, of why nations fail: “not the ignorance of politicians but the incentives and constraints they face from political and economic institutions in their societies” as the institutional economist Acemoglu has correctly argued. To rephrase slightly, not ignorance of good policies, but flawed and inappropriate institutions, or, where the appropriate institutions exist, as they often do in Jamaica, institutional incompetence, and bad politics. The urban upgrading approach to the problem of urban slum communities was a well-conceived programme, with numerous successful applications around the world (World Bank 1999-2001). Our application was carefully thought through, and based on thorough research and planning, involving the participation of local leaders, and a survey of the views of members of the community. When asked which they would prefer—a shot at an apartment in a housing project or an upgraded community—the overwhelming majority choose the latter.

The institutions needed to launch the programme were already well in place: there were many departments of the Ministry of Housing and the Ministry of Local Government, manned by numerous employees with the requisite paper qualifications, dedicated to improving the condition of the urban poor. There was the institution of the Worker’s Bank. There was the Small Industries Development Division of the Jamaica Industrial Development Corporation. And there was the Urban Development Corporation, a big-thinking, public sector organisation “charged with preparing, developing and implementing plans for urban development, urban renewal and rural modernisation, in collaboration with other agencies”. We were given the authority to draw on all these institutions. But while they existed organisationally, were comfortably quartered, with well-paid and ‘qualified’ staff, they were of little help to us.

The most serious problem, however, was the lack of political will. The Kingston urban upgrading project did not work primarily because the politicians involved did not want it to work or were pressured by alternate demands and constraints to make decisions detrimental to the project. The Minister of Housing, as we pointed out, wanted the project to fail although he had promised the prime minister that his ministry would do everything to assist us. He wanted failure partly because of his misguided, and cynical, commitment to the “socialist” ideal of a two-bedroom unit for every family in the slums, which was good for his stump speeches, because housing projects were a political gold-mine, a way of locking in the votes of the party faithful and of displacing non-supporters as well as the mass of politically indifferent community residents. The prime minister, originally all in with the programme, gave in to pressure from local leaders and political henchmen who viewed a housing project as the best way to generate jobs in his constituency during a period of depressed economic conditions and public contestation with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and as a way of rewarding aides in preparation for the upcoming political election. Like the nation at large, then, the urban upgrading project failed because available institutions did not work due to the country’s chronic “implementation deficit” (Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2016) and because of contradictory political aims and decisions.

Finally, I come to what has been, and remains for me, one of the most difficult experiences to write about: my relationship with and view of Michael Manley presented, indirectly, in chapter 8 through the forward to his daughter’s memoir of him. The programme we pursued was, perhaps too grandly, called democratic socialism. It was, in fact, straightforward social democracy, modelled almost in its entirety on the programme of the British Labor Party and other left of centre parties in Europe. That, however, was not how it appeared to the island’s bourgeoisie or the American CIA, this being the height of the cold war and the Latin American and Caribbean adventures of Fidel Castro.

Our failures were largely self-inflicted. We tried to move too far too fast. Our problem was not primarily a lack of funds. Our problem was an inability to follow through with the numerous projects we instituted, some of them half-baked, nearly all lacking in capable leadership. The paradox, and tragedy, of radical change, at least in the Caribbean, is that you can’t run a revolution without people to manage it; but a revolution is exactly what is guaranteed to send the managers fleeing, especially when it was a virtual mark of status among the Jamaican bourgeoisie to have a home and bank account in not so distant America.

However, the movement’s biggest problem may well have been Manley himself, the charismatic leader par excellence. It was a sight to behold him holding a crowd in spellbound rapture and adulation. And yet, he could be quite distant in personal interactions unless he was making an effort to charm you to his point of view. He loved the people; he was rarely at ease with ordinary people. He was at heart an intellectual; my most animated discussions with him were about ideas rather than the details of the policies I was involved with. His public life was one of utmost propriety, honesty and integrity and, unlike nearly every Third World leader of his day (and now) he left office with less money than he entered, in fact, nearly broke. But his private life was one of ruthless selfishness and sexual corruption. With the exception of two of his five wives– the beautiful one who died young in his arms, the other older one in whose arms he died– he broke the heart of nearly every one of the many wives and lovers who succumbed to his irresistible charms. And that, alas, was equally true of his daughters.

I was so perplexed by Manley that I have never been able to write directly about him. It was not until his eldest daughter, Rachael, a remarkably talented memoirist and novelist, honoured me with the request to write the forward to her deeply revealing memoir of her father’s dying days that I found the will to write about him. I was able to do so, indirectly, in the wake of the hauntingly beautiful prose that carried her memories of life in the ebbing slipstream of her father. I did not have much to add to her revelations, really, but what little I did is about all I ever wish to say about the man that so confounded us.

However, my book did not end on a pessimistic note and I, therefore, want to conclude by briefly asking what were the factors accounting for our global successes? Are there things they have in common that we can learn from in fixing our many problems. Let’s take the remarkable, globally outstanding public health campaign and institution building that led to our surprisingly high life expectancy. The historical demographer, James Riley, found that the most important factor explaining this health revolution was the cooperation, participation, and resilience of the Jamaican people who energetically engaged once they realised that it was to their own benefit.

“Among the people the British regarded as willful and disobedient, the essential steps were taken by self-reliant Jamaicans, who decided to become better informed about hygiene and health and to have their children learn about these things, who agreed to build latrines with locally available materials, and who cooperated with the new public health authorities and modified their own behaviour in many ways” (Riley 2005:131).

One basic principle that informed the campaign was this interaction of top-down with bottom-up leadership. Another important reason for the success of the programme was that it was a classic case of participants learning by doing. As the economist, Kenneth Arrow pointed out long ago: “Learning is the product of experience. Learning can only take place through the attempt to solve a problem and therefore only takes place during activity” (Arrow 1962:155). The leadership of the public health movement mobilised a large number of modestly educated black Jamaicans – low-level clerks, parochial workers, agricultural field officers, pupil-teachers, practical nurses, small farmers — to educate the masses. By this means, they learned by doing public health management and were eventually in a position to lead and educate others to work toward better health on their own.

There is much that Jamaican leaders can learn from this ground-level success from the late colonial past. Writing recently on institutional learning and change, a group of development researchers (Watts et al: 2003) at a Dutch research centre, set out a framework for successful development practice that includes the following: the importance of partnership and grass-roots participation, what others have described as the interaction of top-down and bottom-up learning; the expansion of the role of teacher and supervisor to those of facilitator and coach; a re-conception of desired outcomes from too rigidly defined objectives, to a focus on processes and capabilities; the treatment of failure as a valued learning opportunity; and seeing change in evolutionary and adaptive, rather than prescriptive and predetermined terms.

We find, in one form or another, similar principles at play in the development of Jamaica’s other successes. Our free press, recently cited as the 6th freest in the world, also illustrate these points. One striking exception to the extractive institutional structures and racial exclusiveness of the colonial era was The Gleaner newspaper, established by two Jewish half-brothers in 1834, some 17 years before the New York Times. It trained generations of mainly self-educated journalists and in 1951 took the historic step of elevating a black journalist, Theodore Sealy, as its editor, in contrast to the virtual lock-out of the majority population from managerial positions at that time. For most Jamaicans The Gleaner and its tabloid evening companion paper, THE STAR, were the only reading matter, books being beyond the economic reach of the vast majority, including primary school students. As a child, my vocabulary greatly expanded by daily reading The Gleaner to my mother while she sewed, and my first published work, a short story, written in my mid-teens, appeared in THE STAR to the horror of my prudish headmaster. The Gleaner, along with its first-rate competitor, the left-leaning Jamaica Observer, and a large number of radio stations, are cornerstones of Jamaica’s free press, and lively civic culture.

Finally, in this little island of endless surprises, there are some new and encouraging signs of hope. In recent years a new generation of young, smart, highly educated and principled leaders have been replacing the post-colonial politicians and businessmen that have made such a mess of the island’s development. They include, in particular, its former and current ministers of finance, Peter Philips (now head of the Opposition party) and Nigel Clarke (Rhodes Scholar with a PhD in mathematics from Oxford), and its young, accomplished Prime Minister Andrew Holness, as well as many executives in the private sector with a newly found sense of the common good (Hamilton, 2017).

Over the past six years they have achieved what was considered nearly impossible in global financial circles: substantially reduced the island’s national debt from a catastrophic 147 per cent of GDP, to a manageable and declining 96 per cent. They did this without any international bailout or reneging on debts, keeping both the IMF and World Bank at bay, while reducing both unemployment and poverty, expanding infrastructure, implementing tax policy reforms, improving the investment climate, and producing a modest return to growth after decades of stagnation (see Clarke, 2019; Collister, 2019).

In 2015 Bloomberg declared the island’s little stock exchange the best performing in the world (Fieser 2015). Jamaica is now ranked the best place to do business in the Caribbean, and among the five best in the world to start a business (Forbes, 2019; Global Banking and Finance, 2018). An important element of this striking turnaround was the revival and extension of the once-moribund social partnership programme, originally adopted from Barbados, into a vigorous oversight committee in which all stakeholders — government, including the two major political parties, business, labour unions, the media and academia — participate, closely monitor and communicate to the public the often painful economic reforms. It is arguably one of the most remarkable current examples anywhere in the world of civil society engagement in national crisis management and development.

This is a good new start for Jamaica, but there is still a great deal to be done and undone, and the downside risks are high, including those from natural disasters that are on the increase due to global warming. It is questionable whether the hungry, angry and violent urban poor are willing to give them the time they need — in spite of these remarkable recent improvements crime still continues to rise. However, they can take heart and find hope in the long-suffering rural half of the population, the vibrant source of so much of the island’s successes, by keeping in mind one of the most famous of their many wise proverbs, which, in defiance of all that they have suffered, still steadfastly avers that: ‘time langa dan rope’.

The above is Part Three of a presentation by Orlando Patterson delivered at a public lecture on the topic ‘Jamaica and its Post-Colonial Predicament’ on November 29 at the Regional Headquarters of The University of the West Indies. Patterson, a historical and cultural sociologist, is John Cowles Professor of Sociology at Harvard University.

Viewpoints is committed to expanding its range of opinions and commentary. Share your views about this or any of our articles. Email feedback to viewpoints@gleanerjm.com.