‘Tief from tief, God laugh’, but what happens when you tief from pikni?

Jamaicans should be asking what their children are missing when they send them to school. Jamaicans and those who govern them have agreed that not all children are worthy of the kind of education that would give them possibility. Though enrolment at primary level runs high at 96 per cent for both sexes, up to last year when children were still sitting the Grade Six Achievement Test, just 37 per cent of students scored 65 per cent or higher in all subjects.

Affording parents have been assured of the status of their children through private schooling or extra lessons. Prep-school students averaged 20 percentage points higher than their primary-school counterparts in all subjects. For every child sitting GSAT who attended private school, 10 attended public schools. Children whose parents are not well off are in the main being prepared for low-paid work and to become or remain sufferers.

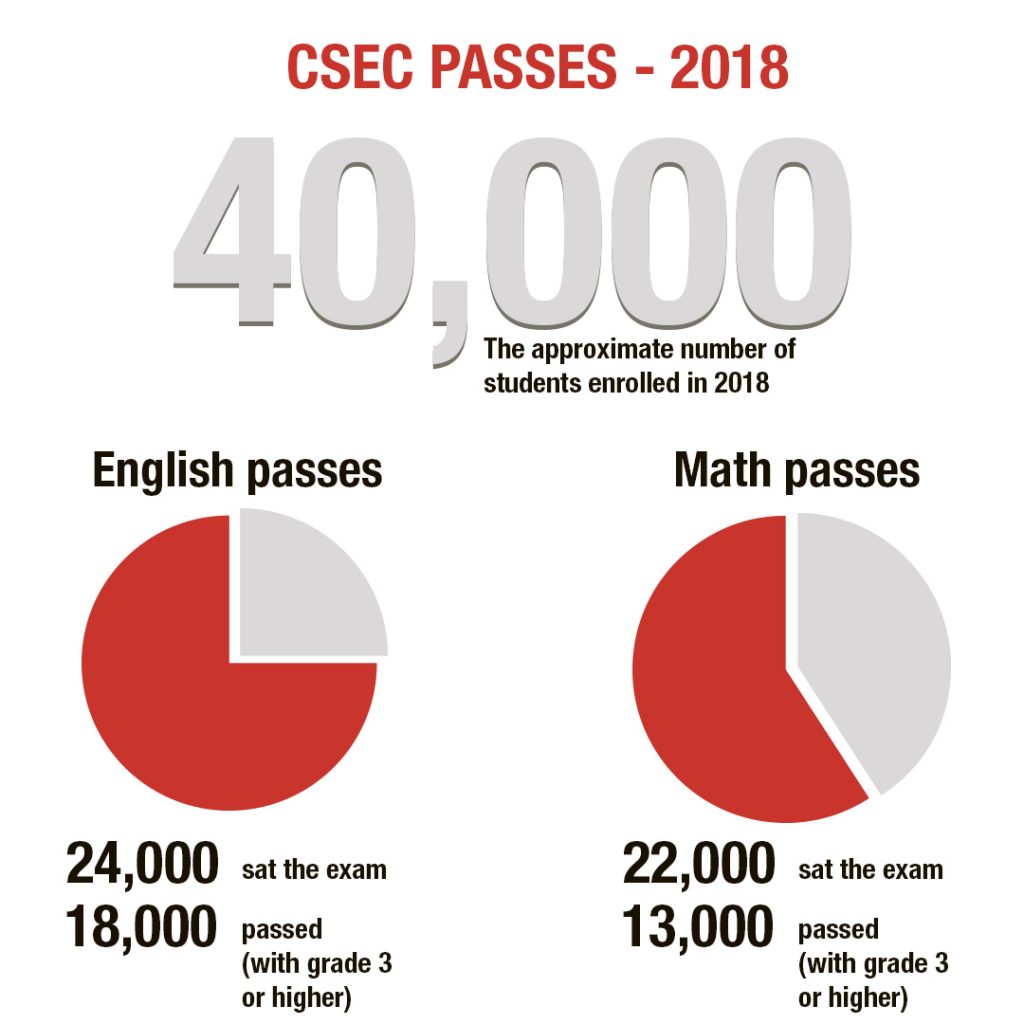

All children get the chance to go to secondary schools, but not all schools are equal. Many drop out of the system before sitting the Caribbean Secondary Education Certificate (CSEC) exams. Nearly a quarter of boys and one-fifth of girls who are old enough to sit CSEC aren’t even registered at school.

The Caribbean Examinations Council says that attaining five or more subjects in CSEC (including mathematics and English) is widely considered to be the benchmark for decent wage employment. Just a quarter of students (more than 60 per cent of whom were girls) achieved this in 2017. Of the approximately 40,000 students who were enrolled in 2018, just over 24,000 sat English; 18,000 passed with a grade of 3 or higher. A little more than 22,000 sat maths, and 13,000 passed. The system produces low levels of literacy and numeracy, possibly because it refuses, in the first place, to acknowledge that Jamaicans are not, at first, speakers of English.

The 2007 report of the Jamaican Language Unit (JLU), The Language Competence Survey of Jamaica, showed that fewer than half of the sample studied were competent in both English and Jamaican (Patwa). Only 46.6 per cent of respondents demonstrated bilingualism. The majority, it said, were “monolingual, with more than a third of this proportion being Patwa speakers”.

People from urban areas in eastern parishes demonstrated slightly higher bilingualism and higher-skilled professionals demonstrated higher bilingualism than the unskilled or unemployed. “English-speaking monolinguals tended to be concentrated in the highly skilled and professional groups.”

The data suggest that social mobility is attached to mastery of English. In spite of this, the Government and people of Jamaica have agreed that education should discriminate against Jamaican speakers in learning English and maths. The JLU has consistently advanced that English should be taught as a second language to improve numeracy and literacy. Meanwhile, the Holness administration recently patted itself on the back for seeking to institutionalise Spanish as a second language when the nation has not even mastered English.

It seems to us that the very purpose of the existing education system is to reproduce the status quo of class in Jamaica. The economy grows on the backs of the poor, on crime, widespread depression, and with little regard for the welfare of people.

We are now concerned that education should make us into productive workers, ‘critically thinking’ for industry (as if we couldn’t already critically think and be self-interested scammers or entrepreneurs), and the cost to Jamaican children is great. Those who can afford it willingly sacrifice their children’s mental health and childhood, shuttling them to extra lessons from Monday to Sunday to ensure that they remain at the top of the productive chain.

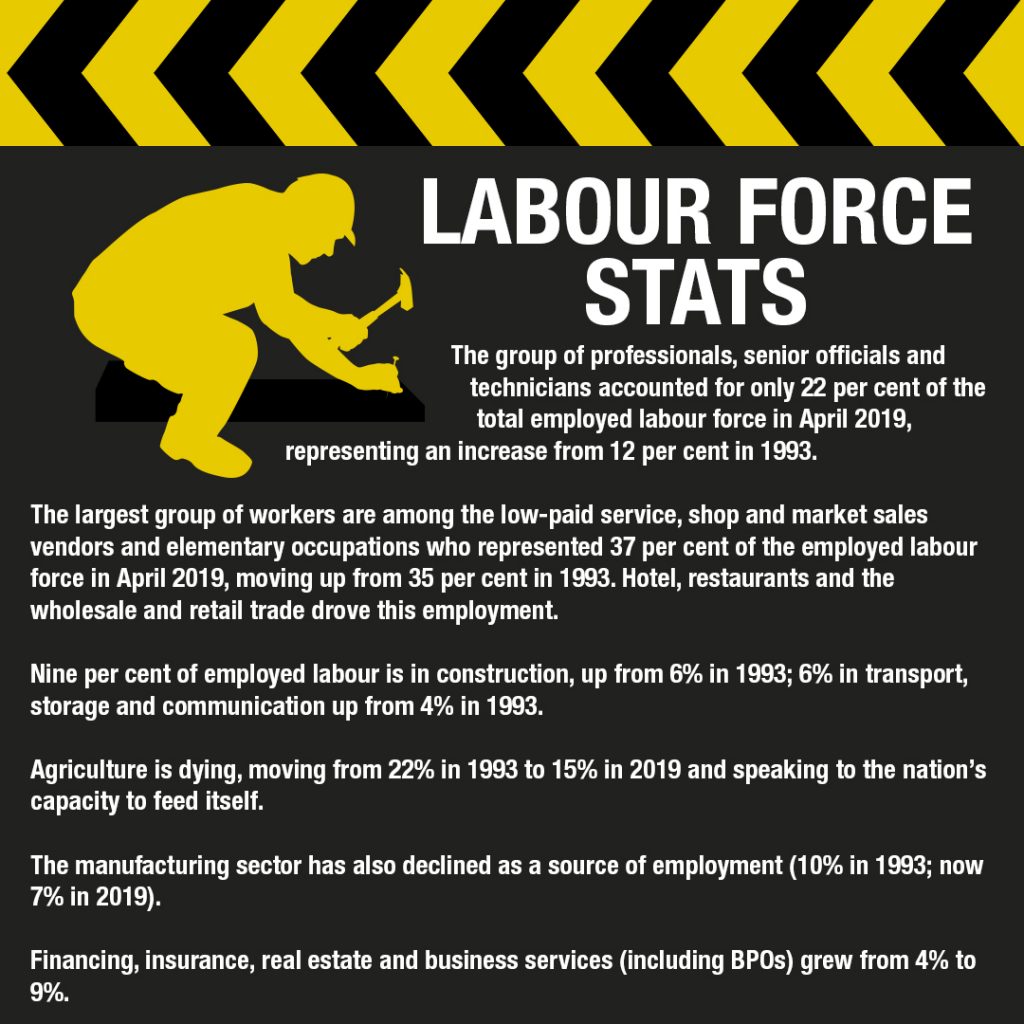

Education should not be outfitted to produce workers for the economy as is. The employment figures do not characterise a highly dynamic economy. While Jamaica’s labour market has seen a shift since the early 1990s, it hasn’t been as dramatic as one might be led to believe. The group of professionals, senior officials and technicians accounted for only 22 per cent of the total employed labour force in April 2019, representing an increase from 12 per cent in 1993.

The largest group of workers are among the low-paid service, shop and market sales vendors and those in elementary occupations who represented 37 per cent of the employed labour force in April 2019, moving up from 35 per cent in 1993. Hotels, restaurants and the wholesale and retail trade drove this employment. Nine per cent of employed labour is in construction, up from six per cent in 1993; six per cent in transport, storage and communication, up from four per cent in 1993.

Agriculture is dying, moving from 22 per cent in 1993 to 15 per cent in 2019, speaking volumes to the nation’s capacity to feed itself. The manufacturing sector has also declined as a source of employment (10 per cent in 1993; now seven per cent in 2019). Financing, insurance, real estate and business service (including BPOs) grew from four per cent to nine per cent.

As is, the Jamaican education system is authoritarian, discriminating and vicious: punishing the ‘bright’ with harder work and disciplining the rest into submission to a dim future. If you are discerning, you might refuse the dimness and choose instead to rely on your wit or your violence to beat the system.

Instead of submission, education should produce possibility. It should cause us to make a link between the fate of the Cockpit Country, the poverty of the already poor and the nation at large and our potential to breathe clean air and drink clean water.

It should bring up children able to imagine different futures and a different Jamaica. Hopefully, not one based on the riches of a few and the poverty of many. Hopefully, they should be able to imagine and create a Jamaica where there is justice, peace, greater equality and, best of all, access to leisure, be it the beach or even a park.

Camilo Thame is a business analyst and data journalist. Maziki Thame teaches political science at Clark Atlanta University. Email feedback to viewpoints@gleanerjm.com.